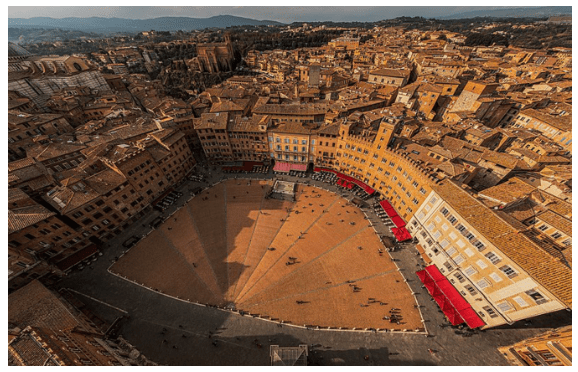

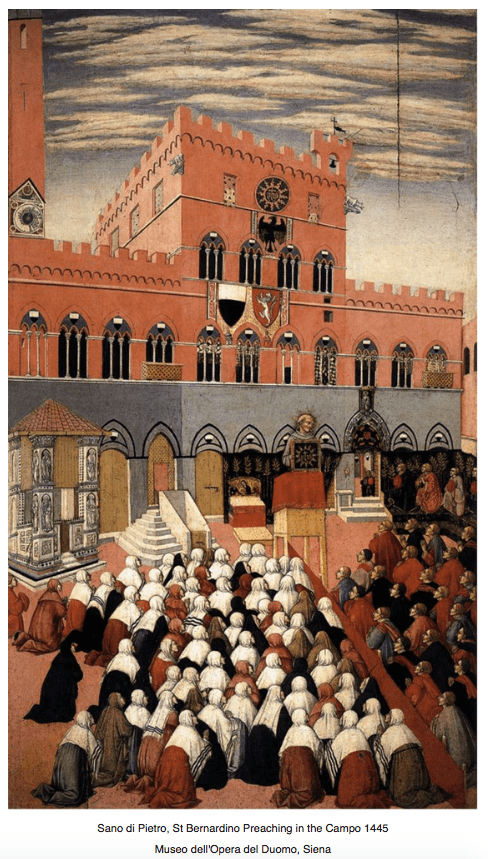

Sitting in the warm tones of tile and canopy in the Campo, the wonderful main piazza of Siena, perhaps with a glass of Brunello di Montalcino in hand, with the majestic Palazzo Pubblico and its soaring 87-metre tower, Torre del Mangia, before you, you may notice two remarkable things. The first is that, unlike other piazze, this one is concave, curved like the inner surface of a bowl, with the great Town Hall actually aligned to its shape. The second feature that springs to mind is the ten lines of white travertine stone set into the Campo beneath your feet, leading diagonally from its edges to the heart of the Palazzo Pubblico itself. As you can see in the illustration above, the ten lines frame nine concave triangles of brick, representing the governing body of Siena, the ‘Nine Governors and Defenders of the Commune and People of Siena’. It is not a stretch to observe that the government of Siena in the form of the Palazzo Pubblico is answering to the people of Siena in the shell of the Campo, and the Campo is answering to the Palazzo Pubblico. The shell gives a sense of containment, of embrace and grace, of security, of being protected, exactly as Siena protected its inhabitants behind its city walls for a thousand years. Here, you can quite easily be transported back to the great age of Siena, the fourteenth century. Indeed the population of Siena now, around 50,000, is almost exactly the same as it was in the early fourteenth century. No wonder UNESCO sees the historic centre of Siena as ‘the embodiment of a medieval city…The whole city of Siena was devised as a work of art that blends into the surrounding landscape’. We finish our glass of Brunello, and go out to explore this enchanting medieval city. Come, time travel with us, while comfortably ensconced in our favourite seats!

The site of Siena was originally an Etruscan settlement that later became the Roman city of Sena Julia at the time of Emperor Augustus. At the centre of vital trade routes, and indeed on the principal pilgrimage route from Canterbury to Rome, the Via Francigena, by the 10c Siena blossomed and acquired great political, economic and medical importance. By the 1300s, Siena was one of Europe’s largest cities and a major military force, in a class with Florence, Venice, and Genoa. The city organised itself into districts, ‘contrade’, within the medieval walls. The walls and the contrade still exist and indeed the contrade still compete against one another in the summer horse race in the Campo, the Palio. They compete, but always with the interests of the republic at heart.

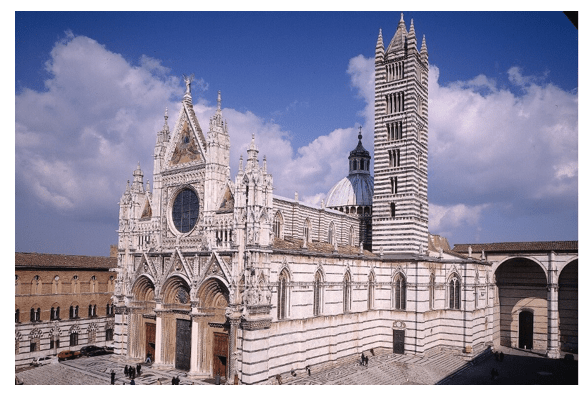

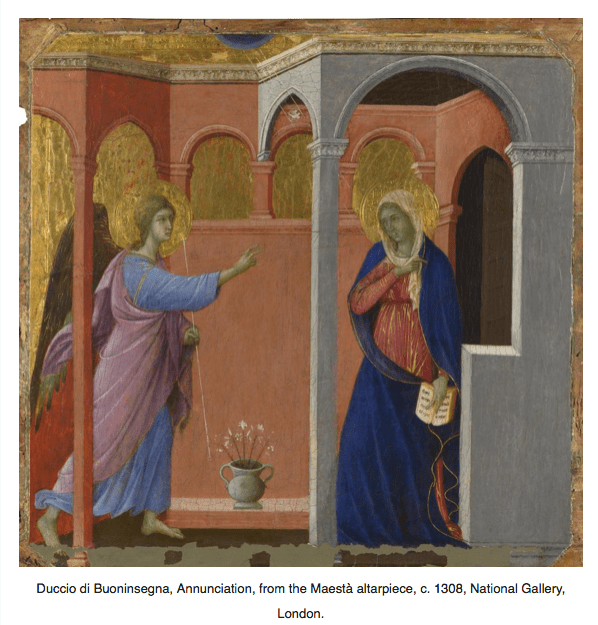

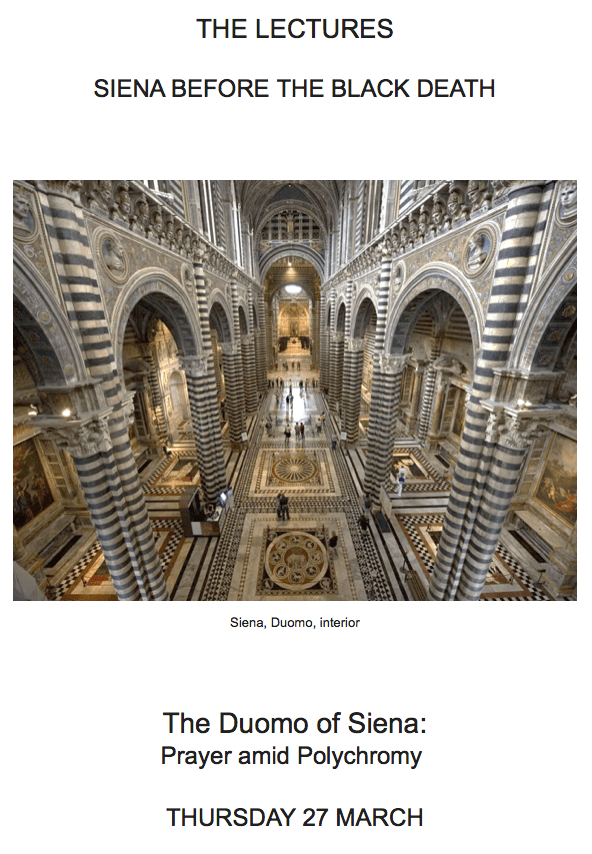

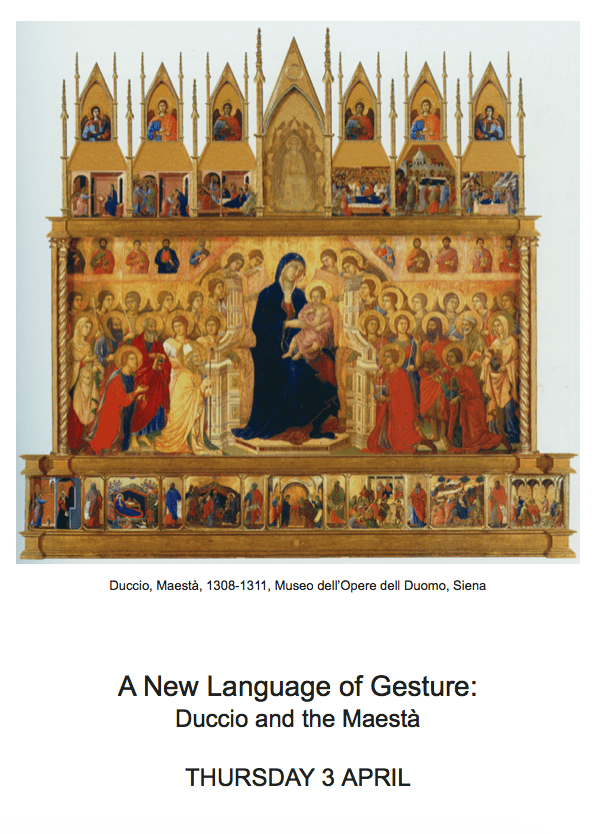

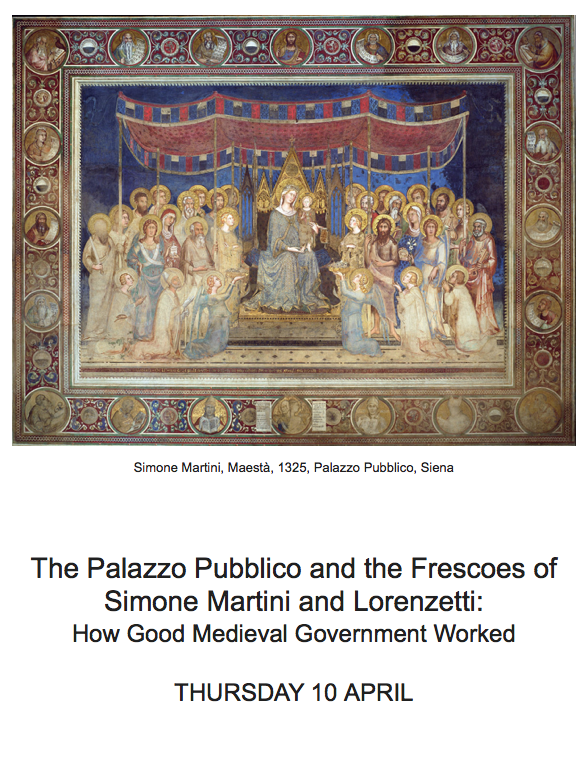

The height of the city’s splendour was reached thanks to the Government of the Nine, which came to power in 1287 and remained in power until 1355. During these golden years, construction began on wonderful monuments such as the Duomo, the Palazzo Pubblico and the Torre del Mangia. Truly great artists such as Duccio di Boninsegna, Simone Martini and the Lorenzetti brothers had the opportunity to express their art in the city, the latter even indicating on the walls of the Palazzo Pubblico through their painted stories exactly how good government can be achieved and the effects that it can have on a population; there are powerful lessons here for modern cities. The pagan symbol of Siena is a she-wolf, fierce in protecting and nurturing her children. The city went further and adopted the Virgin Mary to give it further powerful feminine spiritual protection.

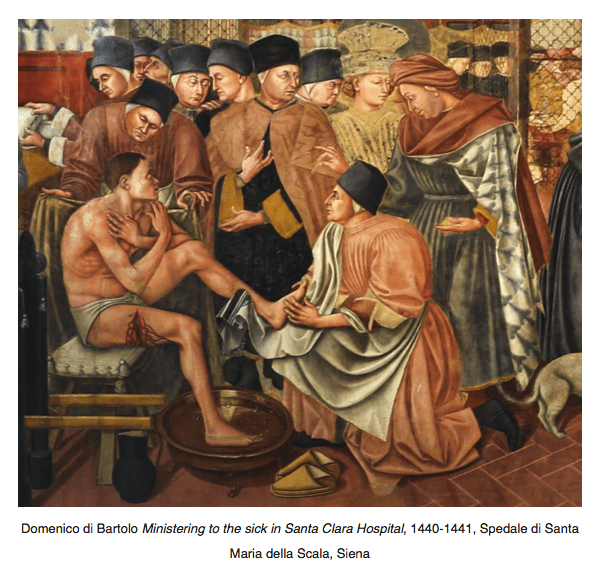

Meanwhile Siena was in the forefront of caring for the sick, with the establishment in the 9c of the Hospital of Santa Clara, which can still be visited. In 1240, the University of Siena, one of the oldest universities in the world, was founded with the Schools of Medicine and Law, giving further protection both to the citizens health and to their need for binding contracts. Sometimes at war with its neighbour Florence, sometimes borrowing artists from it (the extraordinary Donatello famously worked in the city), Siena did everything it could to establish its distinction from that perhaps more macho energetic neighbour, particularly in art. Many aficionados feel more at home with the artistic productions of Siena, their colours and serenity magically soothing to fretful brows.

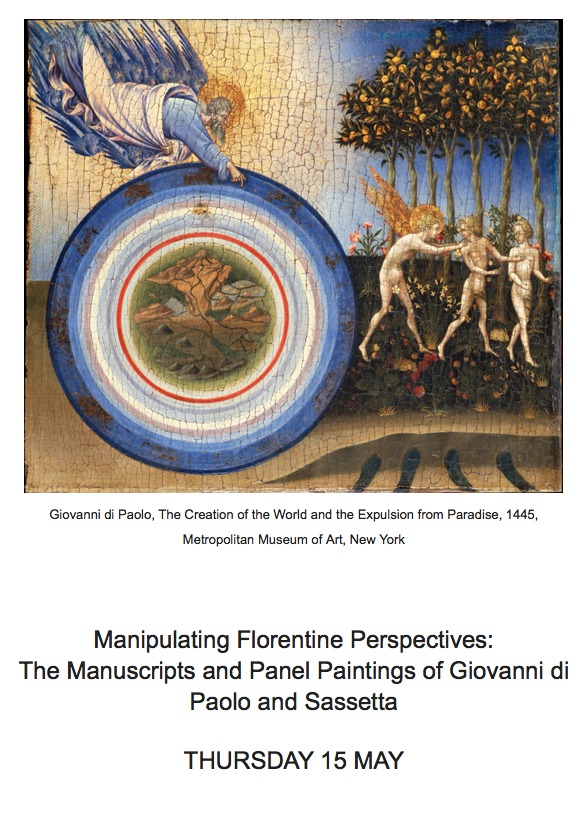

Siena’s painting and sculpture make eloquent, passionate gestures aimed at capturing the truth of the emotions of the figures depicted. When they adopted Florentine developments such as linear perspective they gave them new meaning, moving beyond the Florentine obsession with precision in measurement towards evocative psychological expression. Always the art of Siena is directed towards the survival of the republic as an organic entity made up of the passionate individual citizenry. As two art historians wrote twenty years ago: ‘Perhaps nowhere more vividly than Siena does art operate as a powerful form of cultural self-definition; in fact, long after the heyday of its territorial expansion, we find Sienese art operating as an ongoing assertion of autonomy, cultural hegemony and resistance.’

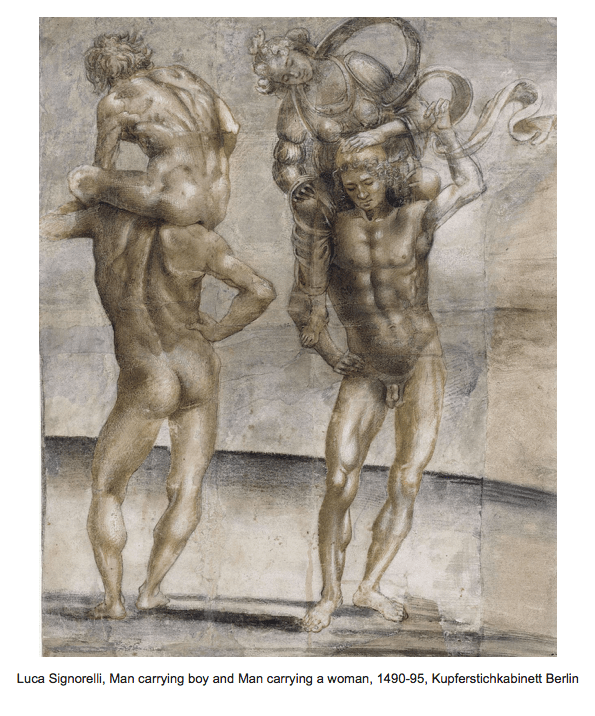

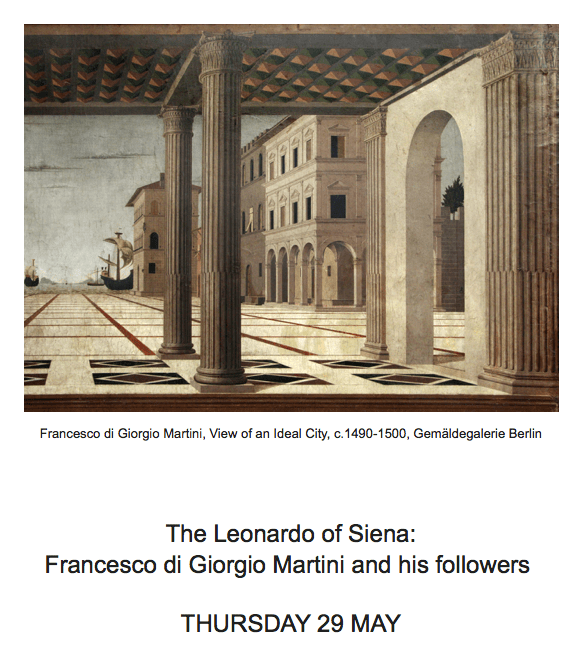

In the mid 14c, the devastating Black Death destroyed three-fifths of Siena’s population. But the city bounced back, and canonised two major modern saints to support it, Catherine and Bernardino, both born in Siena in the 14c. These two, along with a new generation of major patrons such as Piccolomini and Petrucci, truly gave Siena its High Renaissance, and artists from elsewhere flocked to it: Donatello from Florence, Liberale from Verona, Signorelli from Cortona, Pinturicchio from Perugia. The city also looked after its own, fostering the career of the ’Renaissance Man’ Francesco di Giorgio Martini, too often overlooked in favour of Florentine artists and truly a Leonardo of Siena, working in a dazzling array of fields as painter, sculptor, architect, engineer and writer.

After our explorations of Siena’s streets with its magnificent art and preserved history, we come back to our seat in the Campo, breathe sighs of contentment and ask ‘how did this happen’? How has this remarkable city survived almost intact from the 14c? It’s a truism that the best conservator is poverty. Siena went into decline from the mid 16c, and its buildings have been protected from much alteration as a result. It could not afford to replace or adapt major buildings, so the magnificent black and white cathedral, the remarkable medieval hospital next door to it, the warm red Palazzo Pubblico and the mighty palaces of great medieval families remain. The city also never suffered the ill effects of an Industrial Revolution, so the buildings are not tarnished by smoke and soot, and was not a target in later wars, so its buildings have neither been razed to the ground nor pockmarked with shrapnel. It is a place which is caught in a beneficent time warp, redolent of a past content in its civic pride.

On 8 March (until 22 June) this year an exciting exhibition opens at the National Gallery. Titled ‘Siena: the Rise of Painting 1300-1350’ it re-unites sections of glorious Sienese altarpieces that are scattered among the great art museums of the west. It represents a rare chance to get a sense of how such altarpieces contribute to our understanding of this remarkable city. We have built our course beginning with the period covered by this exhibition, but then stretch way beyond it into the highly original later Renaissance of Siena in the 15c and 16c. We hope you will join us for a visit to the ground floor galleries when Nicholas returns in the spring.

Booking Information:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

‘Siena’ is a zoom course which has been developed by Louise Friend and will be presented by Nicholas Friend. It is held on Thursdays, beginning on Thursday 27 March 2025 at 5 pm and ending on Thursday 5 June 2025 at 5 pm. Please note the time of 5 pm: Nicholas will be lecturing from California (at 9 am his time) for some of the duration of this course.

If you book for the course but cannot manage a particular date, then be assured we will be sending recordings of sessions to all registered participants. Each session meets from 15 minutes before the advertised time of the lecture, and each lasts roughly one hour with 15 minutes discussion.

COST: £500 for all ten for members, £600 for all ten for non-members. All sessions are limited to 21 participants to permit an after-lecture discussion session.

Please make your payment to Friend&Friend Ltd by bank transfer to our account with Metrobank, bank sort code 23-05-80, account number 13291721 or via PayPal to nicholas@inscapetours.co.uk, or credit/debit card by phone to Henrietta on 07940 719 397. She is available on Tuesdays or Thursdays between 2-5 pm.

How to Set Up a PayPal account::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Click on this link: https://www.paypal.com/uk/home

In the upper right-hand corner of the screen, click “Sign up.”

On the following screen choose “Personal account” and click “Next.”

On the next page, you’ll be asked to enter your name, email address and to create and confirm a password. When finished, click “Next.”

Click “Agree and create account” and your PayPal account will be created.

How to Connect your Bank Account to your PayPal account:::::::::::::::::::::::

Log on to your account and click the “Wallet” option in the menu bar running along the top of the screen.

On the menu running down the left side of the screen, click the “Link a credit or debit card”.

Enter the card information you wish to link to your PayPal account and click “Link card” for debit card.

How to Send Money::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Log on to your account. Click Send & Request.

Enter the email address of the person you wish to send money to: nicholas@inscapetours.co.uk

Type in the amount you wish to send, click continue then press ‘Send Money Now’.