‘In a period of three centuries, from 1050-1350, several million tons of stone were quarried in France for the building of eighty cathedrals, five hundred large churches and some tens of thousands of parish churches. More stone was excavated in France during these three centuries than at any time in ancient Egypt… Jean Gimpel, ‘The Cathedral Builders’, 1959

Gothic Cathedrals inspire awe in the souls of the most indifferent amongst us; they never fail to stretch the imagination, nor confound the mind by their technical daring and sheer scale. Their height alone, whether experienced while standing inside under a soaring nave or outside approaching the great entry doors, makes one gasp in admiration. There are no buildings in modern times to match them, not even the tallest skyscraper. It is not surprising they still dominate many of their cities of origin, whether Canterbury or Chartres, Salisbury or Strasbourg.

This short course is designed to roll back the hands of time to reveal the processes by which these mighty structures were built from initial sketch to the final installation of altar cloths. Along the way we will examine: the complex motivations of their patrons for their erection, the intricate process by which the architect was chosen, the creation of a workforce with a wide range of skills and aptitudes, and the necessary gathering together of building materials, tools and machinery needed for such a monumental undertaking.

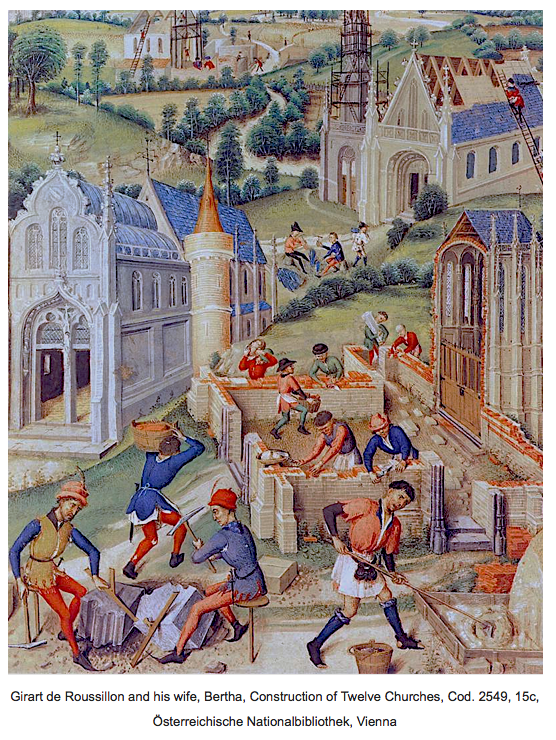

We can view Gothic building sites in astonishing detail in medieval manuscript illuminations of this period. It is these primary sources to which we shall turn for the documentation of the methods used in each stage of the building of a great cathedral whether in Europe or Britain. A wealth of material is depicted in these colourful and engaging illustrations.

We will range in our studies from French to English, to German and Italian cathedrals, seeing the ways each culture had slightly different ways of affirming their destiny in stone while sharing the vocabulary of Gothic architecture. We hope you will each join us for what promises to be a most unusual approach to the understanding and appreciation of these elegant and entrancing ecclesiastical structures.

The Middle Ages were characterized by the diversity of their patrons. The vast sums required for these mighty buildings, usually taking more than a lifetime to build, came from a variety of sources: the bishop, if he were wealthy enough; cathedral canons with rich livings looked after by poorly-paid vicars; community members and guilds; pilgrims attracted by relics; and the sale of indulgences, particularly important after 1263 when Pope Urban IV offered wealthy donors remission for one year of the temporal effects of sin, i.e. time spent in Purgatory. The instigating patron, often the bishop, was decisive in the creation of a building: originated the project, and provided the funds. He chose the architect and insured the continuity of the works. Over all these buildings hover the shadows of exceptional men, and in one well-documented instance, a woman, Bertha de Roussillon.

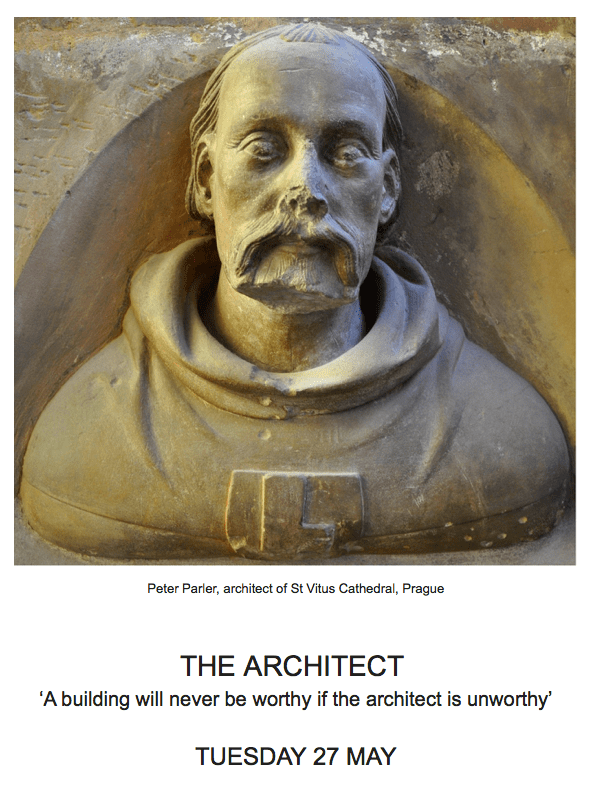

The architect was not only a master builder, but an intellectual, a man possessed of scientia or specialized knowledge. We are increasingly aware of their names, sometimes even of their appearance, as the architect of St Vitus Cathedral in Prague, seen above. Garin in Verdun in 1131 was said to be more learned than Hiram of Tyre, builder of the temple of Solomon. William of Sens, and, then William the Englishman introduced flying buttresses into England at Canterbury Cathedral. Villard de Honnecourt in the 13c left us drawings and building instructions, even though no building has been proven to be designed by him. Arnolfo di Cambio was master of works for Florence Cathedral in the time of Giotto. Henry de Reyns was one of three principal architects of Westminster Abbey, and brought to its distinctly French style his experience of the cathedrals of Reims, Amiens and Chartres.

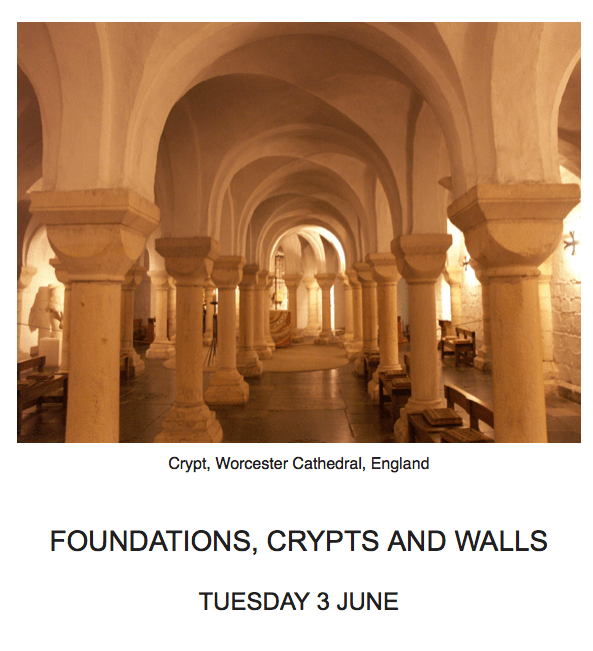

Salisbury Cathedral was built on a swamp, Canterbury on top of the walls of the previous cathedral. Many cathedrals, such as Notre Dame and Chartres, were built on top of the crypts of earlier buildings. The site of Amiens was on a high water table, and so the cathedral was built with caissons, diving bells lowered to the soil beneath the surface. Crypts are often fascinating, because they may predate the cathedral above them, and astonish us with the weight they carry. The marvel of the walls of a Gothic Cathedral is not just the beauty of the right-angled ashlar blocks on the exterior, but the staggering complexity of each block supporting the interior nave arcades, with each colonette reaching upward to support a rib on the vault. Each individual block would have a foliate profile of remarkable complexity, all achieved miraculously by masons with the most basic tools.

Gothic Cathedrals are masterpieces of illusionism. Looking up from the interior, you think you are looking at the underside of the roof supported on slender columns of the arcades and ribs of the stone vaults. Not so. The vaults do not support the roof, which is an entirely discrete entity, raised often high above the vaults and built before them. The structure of the timber supports may be of staggering complexity, as carpenters provide for stresses from the lead sheet cladding of the roof. The massive weight not only presses downwards, but because rooves tend to be angled, it presses the roof outwards. Tiebeams will be fitted to prevent this splay, which then pull the roof together but also push it upwards, necessitating tying the roof down as well.

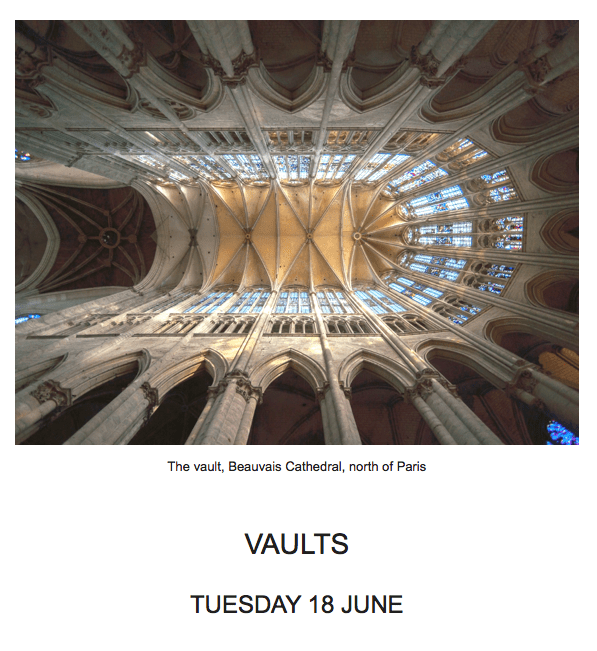

Vaults, built after the rooves were finished, are truly the miracles of Gothic architecture. Those at Beauvais, the tallest, are 157 feet high. They appear impossibly light, and yet being made of stone, they cannot be. How were they built at such heights, and why do they not plummet to the floor? The answer lies within the use of scaffolding erected by the least-recognised craftsmen on the building site. Everything, walls, rooves and vaults, depended on them. The higher the scaffolding went, the stronger the base needed to be and the more intricate the bracings and cross-bracings required. Then carefully-crafted formwork was required to support the ribs and the vaulting stones before the keystones were in position, and then all being well the vaulting would stay aloft. But most great Gothic vaults are still standing, tributes to the sheer genius of their architects, and the consummate skill of their workers.

Central to the creative ambitions of the self-proclaimed inventor of Gothic architecture, Abbot Suger of St Denis, was the need to increase quantities of light in the building in order to symbolise the light of Jesus. The solution lay in the Gothic style of pointed arches that removed the need for heavy walls supporting the rooves, which instead could be supported on slender colonettes. Between those, vast areas of glass could be supplied, stained and painted with dazzlingly vivid imagery designed with complex programmes of narratives and iconography. Patterns of leading lines contributed to the beauty of the effect. Constructional skills were vital even here, for the elaborate foliate tracery of such windows needed to support any wall areas above them: these windows were often works of staggering engineering skill in order to produce an hallucinatory effect.

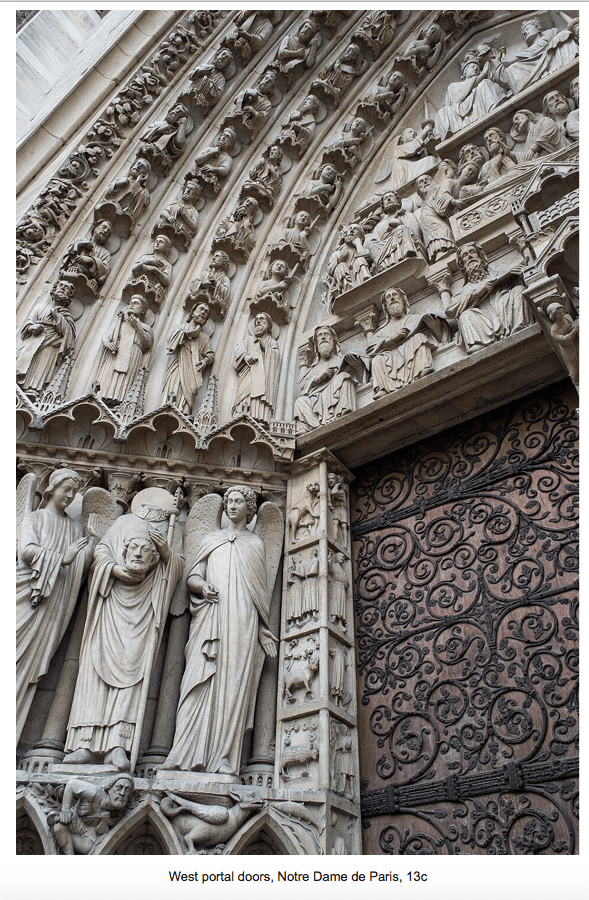

Doors to Gothic Cathedrals were symbolic of the passage to new life through the Mass. Such rites of passage were depicted as rich figurative sculpture, carved from softer limestone than that used for the main structure of the building. Whole programmes of sculpture were meticulously designed to warn you of the dangers of the world and of the rewards that awaited the faithful in heaven. At the same time, such sculptural programmes could answer to the needs of secular patrons, with extensive groups of Old Testament Kings reflecting favourably on the modern, earthly kings who had given rise to their sculptured effigies. Gazing down at us as we enter, their effect can move the most atheist of souls. On the wooden doors themselves foliate ironwork hinges hold together the planks of the doors, with leaves so lifelike and infused with energy you are persuaded to reconsider the skills of the blacksmith and see them as those of an artist.

Booking Information:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

‘The Cathedral Builders’ is a zoom course which has been developed by Louise Friend and will be presented by Nicholas Friend. It is held on Tuesdays, beginning on Tuesday 20 May 2025 at 5 pm and ending on Tuesday 1 July 2025 at 5 pm. Please note the time of 5 pm: Nicholas will be lecturing from California (at 9 am his time) for the duration of this course.

If you book for the course but cannot manage a particular date, then be assured we will be sending recordings of sessions to all registered participants. Each session meets from 15 minutes before the advertised time of the lecture, and each lasts roughly one hour with 15 minutes discussion.

COST: £350 for all seven for members, £420 for all seven for non-members. All sessions are limited to 21 participants to permit an after-lecture discussion session.

Please make your payment to Friend&Friend Ltd by bank transfer to our account with Metrobank, bank sort code 23-05-80, account number 13291721 or via PayPal to nicholas@inscapetours.co.uk, or credit/debit card by phone to Henrietta on 07940 719 397. She is available on Tuesdays or Thursdays between 2-5 pm.

How to Set Up a PayPal account::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Click on this link: https://www.paypal.com/uk/home

In the upper right-hand corner of the screen, click “Sign up.”

On the following screen choose “Personal account” and click “Next.”

On the next page, you’ll be asked to enter your name, email address and to create and confirm a password. When finished, click “Next.”

Click “Agree and create account” and your PayPal account will be created.

How to Connect your Bank Account to your PayPal account:::::::::::::::::::::::

Log on to your account and click the “Wallet” option in the menu bar running along the top of the screen.

On the menu running down the left side of the screen, click the “Link a credit or debit card”.

Enter the card information you wish to link to your PayPal account and click “Link card” for debit card.

How to Send Money::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Log on to your account. Click Send & Request.

Enter the email address of the person you wish to send money to: nicholas@inscapetours.co.uk

Type in the amount you wish to send, click continue then press ‘Send Money Now’.