No decade has been more creative in adversity than the years between the morning of the Wall Street crash, Thursday 24 October, 1929, and Sunday morning 3 September 1939 when Chamberlain broadcast the news that Britain was again at war with Germany.

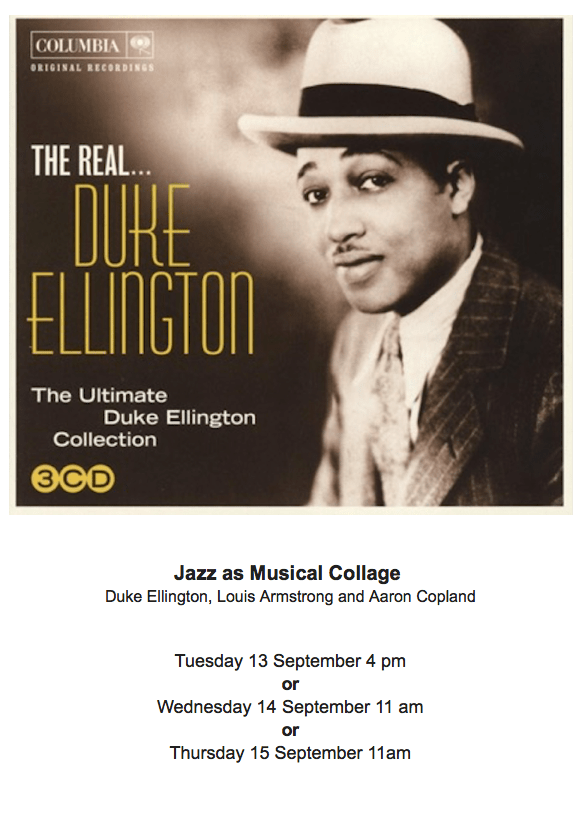

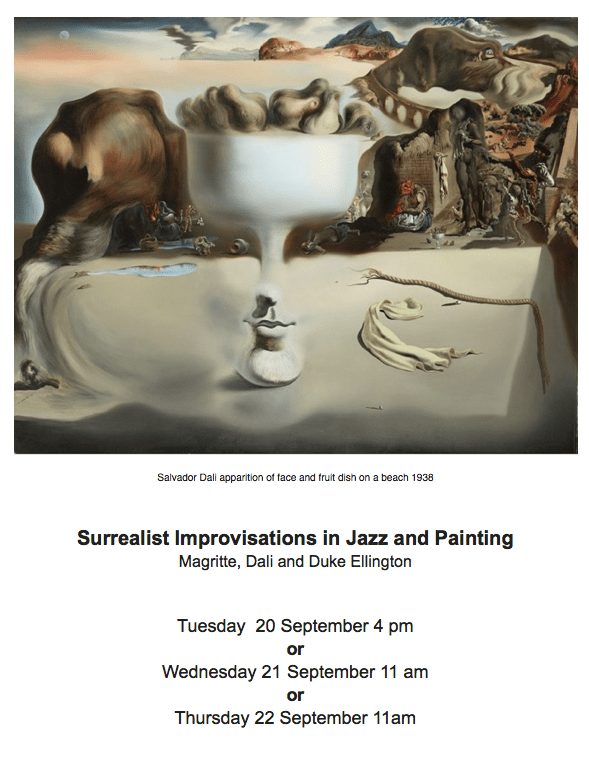

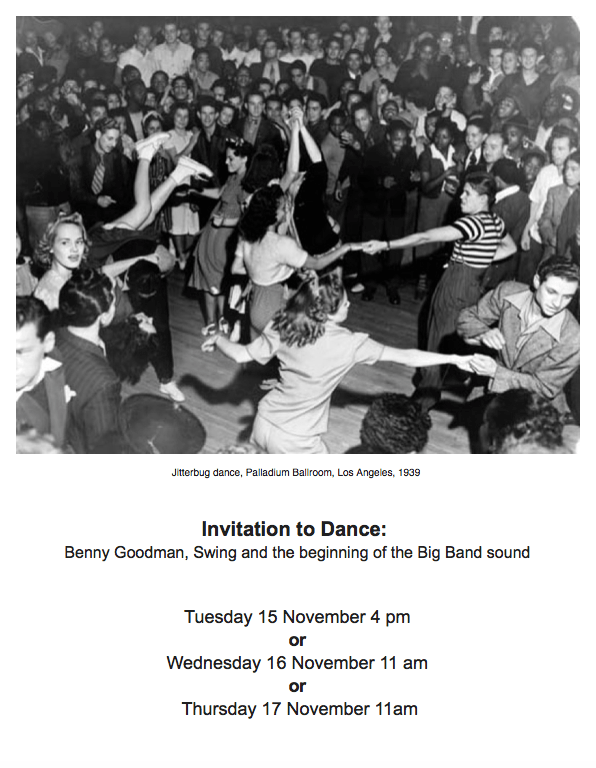

That announcement was not unexpected. Many recognised that due to the misguided drafting of the Treaty of Versailles after the First World War, and the crippling reparations that were forced upon Germany, Europe was simply simmering before the next war boiled up. Yet despite the anxiety of the period ‘entre deux guerres’ as TS Eliot put it, the Thirties was a decade in which creative minds were motivated to produce some of the most adventurous work of the entire 20c. It is not an exaggeration to suggest that these minds, in both the sciences and the arts, were guided by a dynamism, a freedom to think beyond convention, a freedom to break the rules that had governed European and much of American protocol. This dynamism first emerged earlier in the 20th century in the brilliant improvisational approach of African-American jazz. The results were thrilling: in the sciences the decade saw the invention of radar, helicopters, electron microscopes and polaroid photography, as well as the world-changing discovery of nuclear fission. In the arts it saw new approaches to subject matter whether reflective of ordinary life as in the art of the Pitmen Painters or in the work of the Surrealists who expressed a vision of the world that reclaimed the suppressed realms of human experience, celebrated the coupling of irreconcilable realities, and welcomed the arbitrary and the unusual. Jazz musicians combined jazz, popular song and dance in the new rhythms of Swing, led by Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman. Filmmakers exploited the new possibilities of ‘the talkies’. Some historians credit sound with saving the Hollywood studio system in the face of the Great Depression. American cinema reached its peak of efficiently manufactured glamour and global appeal during this period.

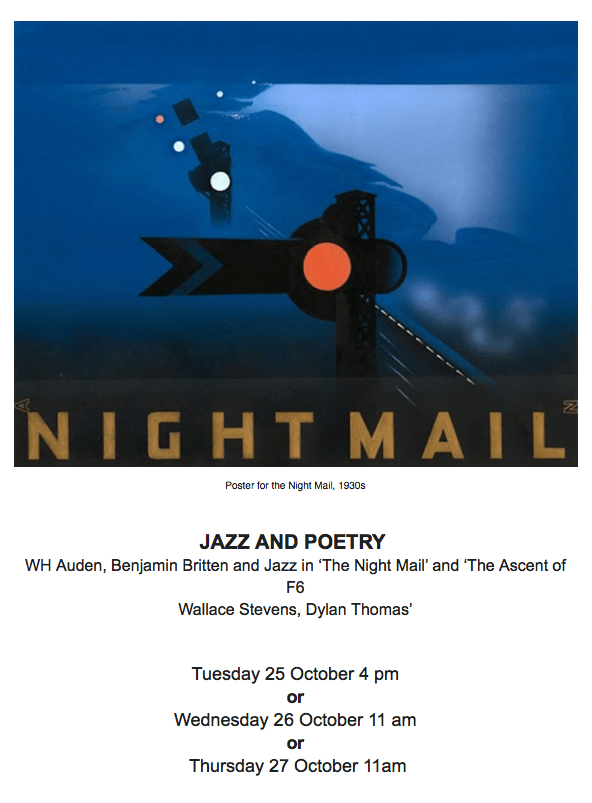

Key to understanding the culture of this remarkable decade are, firstly, social, creative and artistic collaboration, and, secondly, the way in which all the arts aspire to the contradictions, disjunctions, and incongruity of Jazz. The capitalist disaster of the Wall Street Crash encouraged new interests in social cohesion through the popular appeal of the arts and music. Administratively, this was expressed in the USA via the Roosevelts’ New Deal and in Britain via Frank Pick’s joined-up thinking for London Transport. New ways of communicating with large numbers of people were made possible by radio, films, sound recordings, and high-quality reproductions in magazines and on posters. These became the media that as Sartre put it were ‘the dreams everyone could dream at the same time’. Meanwhile, individually creative artists and scientists made new discoveries through collaborations between the sciences and the different arts. Painters found new subject matter in what could be witnessed in scientific discoveries via the microscope or telescope or by giving pictorial form to the psychologist’s new discoveries of tales of the subconscious. New partnerships emerged between, for example, the post office, the poet WH Auden and the composer Benjamin Britten in their wonderful jazz-inspired ‘Night Mail’. The composer Aaron Copland, markedly influenced by jazz, collaborated with the choreographer Eugene Loring on his 1938 ballet ‘Billy the Kid’. George Gershwin and his brother Ira Gershwin wrote some of the most sublime music of the 20c. Analogies can be made between the surrealism of 1930s painting and Duke Ellington’s ‘One O’clock Jump,’ and between regionalist painting and the culture of the musical outcast represented by Django Reinhardt and Billie Holiday. Martha Graham’s utterly revolutionary style of dance can be compared to the inventiveness of 1930s sculpture by Naum Gabo. The language of Art Deco can be found equally in furniture and poster design as well as in modernist architecture, while some of the characteristics of those buildings, particularly cinemas, can be compared to the exhilarations of jazz.

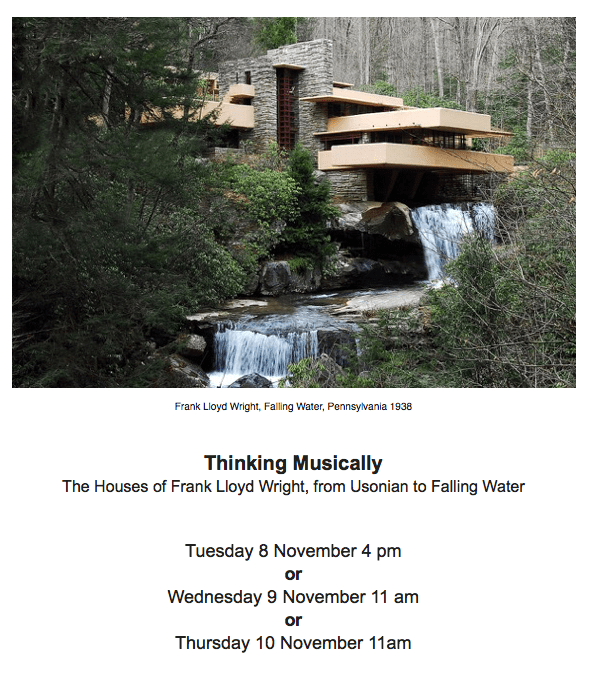

Above all, the arts of the thirties seem truly to have ‘aspired to the condition of music’, to quote Walter Pater. The great architect Frank Lloyd Wright, each element of whose buildings seems to act as a player in a band, remarked ‘… Never miss the idea that architecture and music belong together. They are practically one.’ and ‘ When I see Architecture that moves me, I hear music in my inner ear’. People found consolation and uplift in the glorious music of Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Django Reinhardt, in the songs of Cole Porter and Noel Coward, and the exquisite voices of Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald.

This unique course on the Jazz Age suggests that jazz lies at the heart of all the arts in the Thirties. It explores their interactions: between jazz and ‘classical’ music, between jazz and popular song, between jazz and dance, between jazz and painting, between jazz and architecture, between jazz and sculpture, to offer a rounded view of the qualities and coherence of this remarkable culture, one so remarkably rich despite the barren economic and social prospects of this third decade of the twentieth century.

Booking Information:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

This online course via Zoom will be presented by Nicholas Friend, Founding Director of Inscape. It begins on Tuesday 13 September 2022 at 4 pm, repeating on Wednesdays and Thursdays at 11 am. It ends on Thursday 17 November 2022.

You may choose to attend all Tuesdays, Wednesdays or all Thursdays, or any mixture of these, subject to availability. You may also choose to attend individual sessions. If you would like to attend but cannot manage a particular date, then be assured we will be sending recordings of sessions to all participants. Each session meets from 20 minutes before the advertised time of the lecture, and each lecture lasts roughly one hour, with around 15 minutes discussion.

Cost: £315 members or £385 non-members for the course of 7 sessions or £45 members or £55 non-members per individual session. All sessions are limited to 21 participants to permit discussion.

Due to the coronavirus cheques are not a viable option at this time. Instead, please make your payment to Friend&Friend Ltd by bank transfer to our account with Metrobank, bank sort code 23-05-80, account number 13291721 or via PayPal to nicholas@inscapetours.co.uk, or credit/debit card by phone to Henrietta on 07940 719397. She is available Tuesdays 10-12 and 2-5 pm or Thursdays 10-12 and 2-5 pm. Do get in touch if you would like extra support learning how to use Zoom.

How to Set Up a PayPal account::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Click on this link: https://www.paypal.com/uk/home

In the upper right-hand corner of the screen, click “Sign up.”

On the following screen choose “Personal account” and click “Next.”

On the next page, you’ll be asked to enter your name, email address and to create and confirm a password. When finished, click “Next.”

Click “Agree and create account” and your PayPal account will be created.

How to Connect your Bank Account to your PayPal account:::::::::::::::::::::::

Log on to your account and click the “Wallet” option in the menu bar running along the top of the screen.

On the menu running down the left side of the screen, click the “Link a credit or debit card”.

Enter the card information you wish to link to your PayPal account and click “Link card” for debit card.

How to Send Money::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Log on to your account. Click Send & Request.

Enter the email address of the person you wish to send money to: nicholas@inscapetours.co.uk

Type in the amount you wish to send, click continue then press ‘Send Money Now’.