What is ‘High’ about the High Renaissance? For those of us in London at the moment, there are ways at hand to launch an unusually lively enquiry. With not just one, but two current London exhibitions, one at the Royal Academy, one at the King’s Gallery, showing major works in drawing, sculpture and painting from that thrilling period in art history, now might be the best time to find out! In an equally timely manner, Inscape offers an alternative to braving streets swarming with holiday visitors or to standing in a congested gallery. We present you with a ten session Zoom course; ten hours of Lectures plus discussion time with Nicholas Friend as your Guide to an immersive experience in this brilliant and complex efflorescence in the history of Western Art.

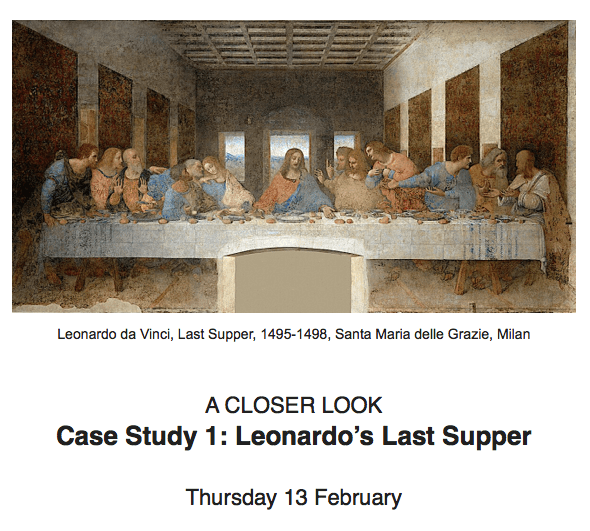

Coined in the early 1800s, ‘High Renaissance’ is used to refer to a period in Italian art beginning around the time of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘The Last Supper’ (1490s) in Milan and ending when in 1527 Parmigianino was found painting his ‘Dream of St Jerome’ in Rome by the troops of Emperor Charles V, sacking the Holy City. Vasari tells the story that the troops were so impressed they let him finish the altarpiece, although he had to pay a ransom to escape Rome…

Artists’ concerns in the ‘Early’ 15c Renaissance, i.e. linear perspective, the creation of form through light and shade, and accuracy in anatomy, were seen to be welded in the ‘High’ Renaissance into a new ordered, symmetrical, breathlessly balanced, harmonious whole. Meanwhile the humanist ideas behind the High Renaissance – the artist as genius, classical art, philosophy and literature as foundational, the individual with agency at the centre of the universe and other related elements we shall discuss – have all deeply informed the social and cultural values of the world ever since.

But in the last thirty years, some art historians have criticized the term ‘High Renaissance’ as being an oversimplification. After all, what is symmetrical or harmonious about the grouping or gestures of the disciples in Leonardo’s Last Supper? What is harmonious about the warriors in his Battle of Anghiari as copied by Rubens, see below?

Perhaps the period of the High Renaissance was not one of harmony, balance and order after all. In fact, the early 16c in Italy was no more ordered a time than our own. In the wake of the reign of Savonarola, and his death by strangulation and burning, Florence was at war with Pisa over access to the sea. Rome was shaken by the loss of papal possessions such as Bologna, and then by passionate attacks on the Catholic Church by Luther. Venice had just had 12,000 troops wiped out by the French King at the battle of Agnadello, and was anxious about Ottoman incursions from the east. Whether from Florence, Rome or Venice, the art of these cities sometimes reflects this turbulence, alongside the harmony to which classically-trained artists aspired in their commissions.

The High Renaissance is not a great period of art just because it champions order, but because its works cover the gamut of human emotions, from distress to joy, anguish to serenity, and, in composition, supreme harmony to extremes of distortion. As in all the best art, we witness markedly human dramas of tension between orderly ideas and irrepressible emotions.

But this is not a tale of dramatic tension in art alone. It is a tale of dynamic relationships between three of the greatest artistic geniuses who have ever lived. What can it have been like for Leonardo, an entire generation older than Michelangelo, to be threatened by his younger rival on the same Florentine turf, when they were each commissioned to paint a battle on a wall in the Palazzo Vecchio? Reportedly Michelangelo mocked Leonardo’s inability to finish projects, and Leonardo mocked Michelangelo’s youthful lack of learning. Leonardo took what we now call a holistic view of the natural world – animal, vegetable and mineral. For Michelangelo human flesh and bones and muscle were the true marvels of the visible world and outweighed all other considerations. Leonardo mocked his rival’s muscular figures as ‘bags of walnuts’. Michelangelo seems to have seen Leonardo as soulless.

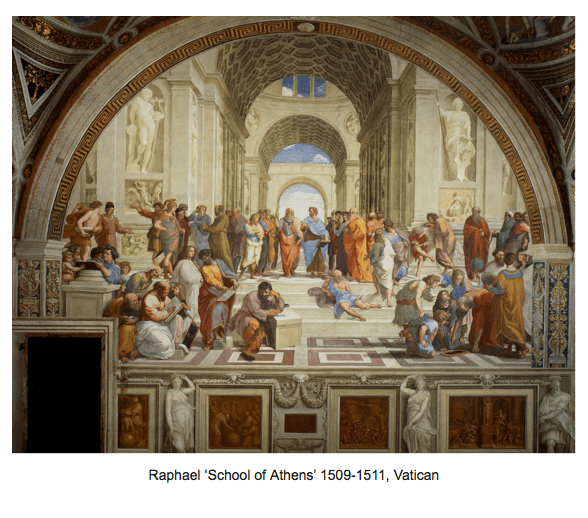

Both of them must have been threatened by the new kid on the block, Raphael, thirty years younger than Leonardo and eight years younger than Michelangelo. They could hardly have been friends: Leonardo so much older, Michelangelo so much more hot-tempered, Raphael reported as being charm itself. No wonder Raphael, in his ‘School of Athens’ depicts Michelangelo as the most depressed man of the Italian Renaissance. Of course it was Michelangelo who was commissioned by Pope Julius II to paint the Sistine Chapel Ceiling. But both Julius II and his successor Leo X found themselves so charmed by Raphael that they gave him, rather than the older rival, commissions for portraits of themselves, for tapestries for the Sistine Chapel which would run the risk of diverting attention from the great ceiling, and for major frescoes in rooms in the Vatican. Twenty-two years after Raphael’s death, Michelangelo is still supposed to have said of Raphael ‘whatever he had of art, he had from me.’

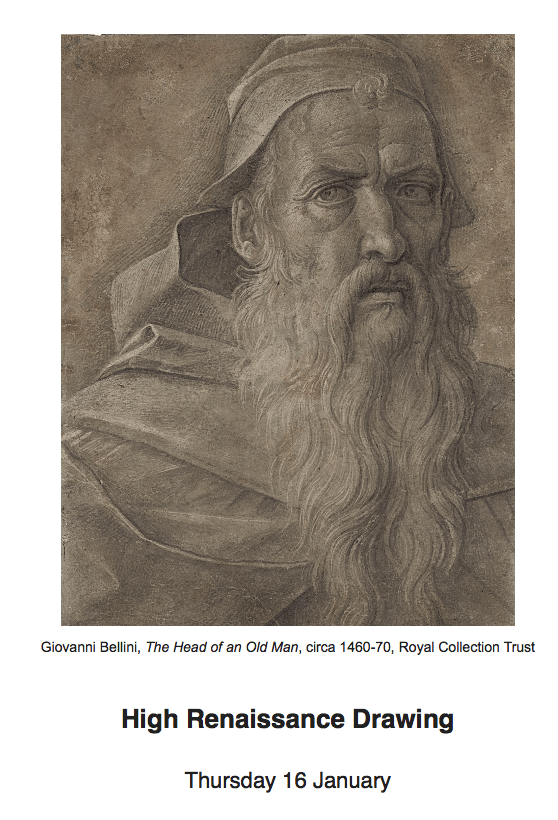

Both London exhibitions include stunning drawings, such as the one above, whose subjects can seem almost to speak to us. For that reason, and because drawings underlie most High Renaissance paintings and sculptures, it is with drawings we begin our course. Their appeal may at first be elusive, but once you have taken time to examine them, there is quite simply no art more rewarding. For here, right in front of you, are the artist’s mind and hand. No intermediaries, no assistants. Just the artist, him or herself, with every mark a thought, a gesture, in the great creative act that somehow conjures three dimensions out of two, sometimes with nothing more elaborate than a piece of chalk or charcoal. In our Zoom sessions, aided by state-of-the-art technology so that we can home in on the tiniest mark, you can actually see minute details hard to make out with the naked eye, let alone when jostling for space with other spectators in an exhibition.

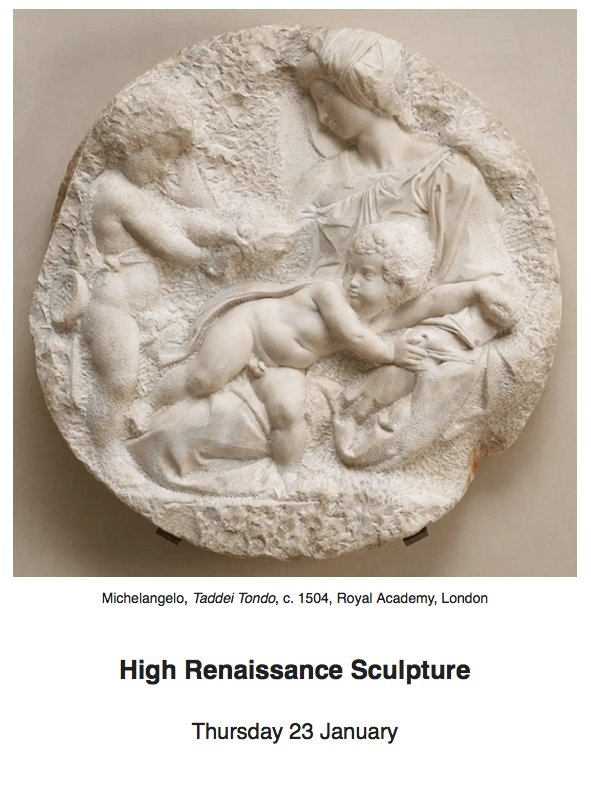

One of the current London exhibitions directly addresses sculpture of the period when exploring the influence on painting of the glorious Michelangelo Taddei Tondo in the RA (above), with the baby Jesus struggling to escape the goldfinch, symbol of the Resurrection, held out by John the Baptist. The theme is picked up by Raphael in the Bridgewater Madonna, now in the National Gallery in Edinburgh, another instance of tension in this world of apparent order.

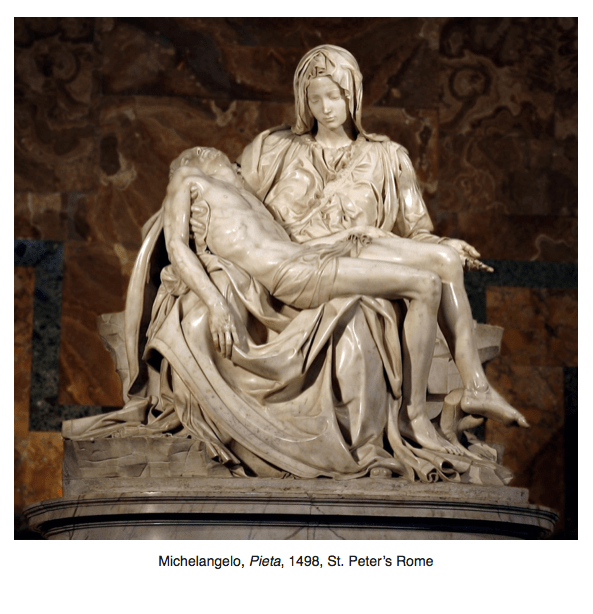

In a similar way, when we look at Michelangelo’s first great masterpiece, the Pietà in Rome, (below) we see boiling draperies, utterly at odds with the serenity of the Virgin’s face. The High Renaissance includes numerous examples of such majestic oppositions in Michelangelo’s sculpture, whether in his ‘slaves’ or his work for Julius II’s tomb, as well as in that of his High Renaissance followers Baccio Bandinelli and Lorenzo Bregno.

It is no accident that the Royal Academy has chosen the year 1504 as the focus of their current show. This was a year of hope for Florence after the disastrous previous decade, one which included the ousting of the Medici, the accession to power of Savonarola the Dominican preacher, and the invasion of Italy by the French King Charles VIII. As the Royal Academy exhibition makes clear, this is the year of Michelangelo’s extraordinary competition with Leonardo in painting battle scenes for the Council Hall in the Palazzo Vecchio, the year of Michelangelo’s ‘Taddei Tondo’ and numerous experiments with compositions it inspired in Raphael when he arrived in Florence in late 1504, and relates fascinatingly to Leonardo’s, probably later, Burlington cartoon of the Virgin, St Anne, the Christ Child and John the Baptist. We use the exhibition at the Royal Academy as a reference for exploring all dimensions of this remarkable year in Florentine history.

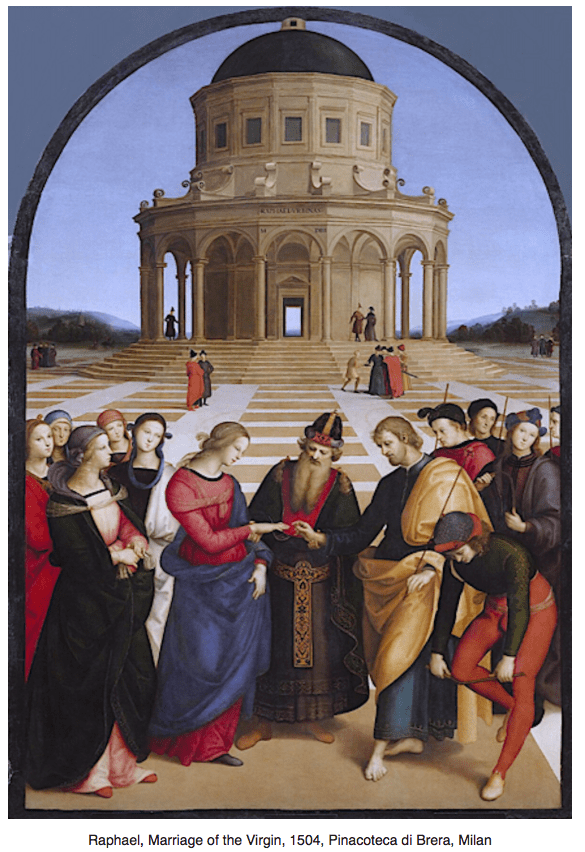

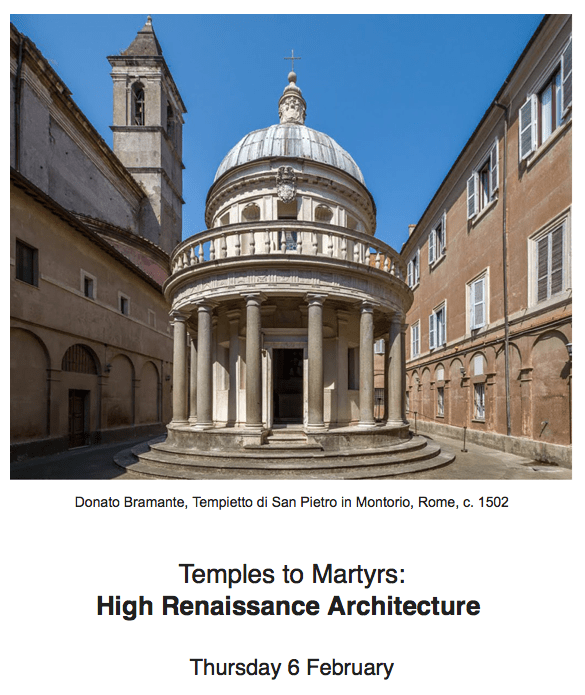

Of all three visual arts, architecture of this period is the one most likely to express balance and symmetry. For religious architecture, balance and proportion inspire confidence. No architect knew this more than Bramante, whose work inspires so much ecclesiastical architecture of later generations, such as Wren’s St Pauls and Hawkmoor’s Mausoleum at Castle Howard. But the beauty of his proportions finds its echo in the painted background architecture in High Renaissance altarpieces and murals, particularly by Raphael and his followers. Indeed, Vasari thought it was Bramante who was responsible for the astonishing architectural grandeur of Raphael’s ‘School of Athens’ in the Vatican (see below).

We discuss the work of Bramante, his followers and disciples such as Antonio da Sangallo, and end with the often thrillingly bizarre solutions to architectural problems of Michelangelo.

We use Google Arts to take a meticulously closer look at this extraordinary mural painted by Leonardo for the refectory of the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. What makes it so remarkable by comparison to previous treatments of the theme? How would it have struck the monks? Does it reflect theological thinking of the time? Which emotion wins out in the end, the balance of Jesus’ pose and the regularity of the architecture on the one hand, or the extreme agitation of the apostles on the other? Can we find such agitation in other paintings of the same decade? Why were copies of this painting distributed among the art academies of Europe?

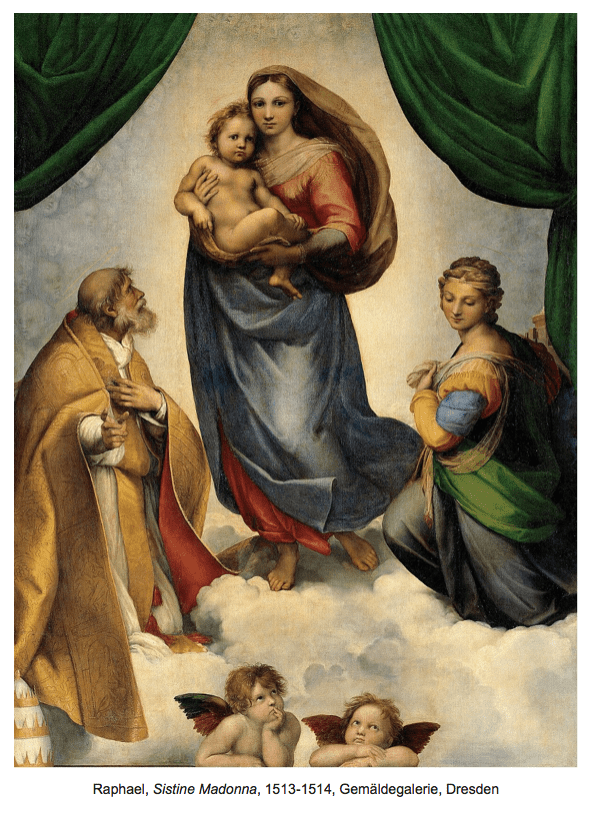

The great Russian 19c novelist Dostoevsky called Raphael’s Sistine Madonna “the greatest revelation of the human spirit”. Dostoevsky was not the first to remark on the power of the work. Only thirty years after Raphael’s death, Vasari wrote that it was “a truly rare and extraordinary work.” The neoclassical 18c theorist Johann Winckelmann was fascinated by it. It had a great influence on the German writer and scholar Goethe, the musician Wagner, and the philosopher Nietzsche. It and other works by Raphael also influenced modern artists like Pablo Picasso, who said, “Leonardo da Vinci promises us heaven. Raphael gives it to us.” The image of the cherubim alone has had an extensive popular culture presence, being featured on contemporary postcards, U.S. stamps, T-shirts, and other consumer items.

Speaking of heaven, the High Renaissance saw the development of ‘heaven ceilings’ by Correggio and his followers. Such painters took advantage of balance in 16c architecture sometimes being expressed in the form of a dome supported by pendentives at each corner. The pendentives, being four in number, lent themselves to Christian symbolism (four Evangelists, Four Gospels, Four Fathers of the Latin Church), while the vaults, by suggesting the heavens, lent themselves to the subject of the Assumption or an Apotheosis. The eye is drawn upward into soaring layers of clouds and figures, the origin of even more majestic Baroque conceptions of the following century.

Correggio’s astonishing ‘Assumption of the Virgin’ for Parma Cathedral was directly informed by contemporary events, notably criticism of the Catholic Church by Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation. Correggio emphasizes the divine authority of the Church, by depicting the Catholic belief that at death, the Virgin was assumed bodily into heaven, a belief not shared by Protestants. Emotionally, the scene presents a joyful reunion of the Virgin with her Son, thus alluding to Parma’s return to the Papal States, and the hope that Protestant congregations would likewise return to the ‘true Church’.

Why were Venetian painters not included in early histories of the High Renaissance? Do the ‘High Renaissance values’ of balance, harmony and symmetry not apply to works by contemporaries of Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo in Venice? If not, why not? What was so different about Venice?

We discover that indeed to be a painter in Venice WAS a very different matter from being a painter in Florence or Rome. If you belonged to the painters’ guild in Venice, then painting was what you did, but in Florence or Rome you might be expected to turn your hand to sculpture or architecture as well, as indeed did Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo, all three. But there was something more to Venetian painting. In the early 16c painters such as Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione and Titian came up with more than their fair share of mystery paintings, like the one above, whose meanings are still being debated to this day, while spectators revel in the glories of their light, their vibrant colour and the softness of their brushstrokes.

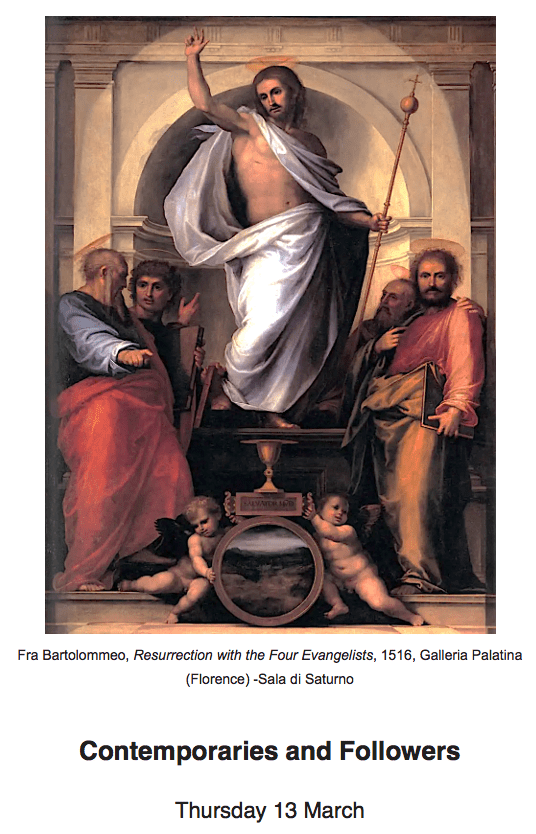

Any discussion of the High Renaissance should not be limited to the ‘Triumvirate’ -Leonardo Michelangelo and Raphael – great though they be. Their contemporaries and followers often move far beyond mere imitation, as they come up with creative expressions unique to them. It is thrilling to discover the muscular energy and curious imagination of Andrea del Sarto, for example, or Fra Bartolommeo’s soft yet grand style, or the ways in which Boltraffio and Luini managed to echo the smoky outlines of their master Leonardo.

After the ‘High Renaissance’, what directions could artists take? Many chose to stretch the limits of all the elements that Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael had made famous: the balance and the anguish, the beauty and the terror, the softness and the harshness, the harmony and the discord.

Our course ends with the period 1515-1570, a period that has been famously referred to as ‘Mannerism’. But that is to do it an injustice. ‘Mannered’ suggests something superficial, affected, but such artists as Pontormo and Parmigianino were far more subtle than that label suggests. They reconsidered subject matter, embarking on oddly proportioned figures to enhance a vision, or showing multiple scenes in one frame to illustrate a complex narrative. Their colouring was sometimes deliberately inharmonious or particularly brilliant, designed to catch the spectator off-guard and make them look more closely. Many of their works have been insufficiently studied, something we aim to correct here and now.

Booking Information:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

What is High about the High Renaissance? has been developed by Louise Friend and will be presented by Nicholas Friend via video (Zoom). It is held on Thursdays, beginning on Thursday 16 January 2025 at 5 pm and ending on Thursday 20 March 2025 at 5 pm. Please note the time of 5 pm: Nicholas will be lecturing from London or California (for the duration of this course.

If you book for the course but cannot manage a particular date, then be assured we will be sending recordings of sessions to all registered participants. Each session meets from 15 minutes before the advertised time of the lecture, and each lasts roughly one hour with 15 minutes discussion.

COST: £500 for all ten sessions for members, £600 for all ten sessions for non-members. All sessions are limited to 21 participants to permit an after-lecture discussion session.

Please make your payment to Friend&Friend Ltd by bank transfer to our account with Metrobank, bank sort code 23-05-80, account number 13291721 or via PayPal to nicholas@inscapetours.co.uk, or credit/debit card by phone to Henrietta on 07940 719 397. She is available Tuesdays 10-12 and 2-5 pm or Thursdays 10-12 and 2-5 pm.

How to Set Up a PayPal account::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Click on this link: https://www.paypal.com/uk/home

In the upper right-hand corner of the screen, click “Sign up.”

On the following screen choose “Personal account” and click “Next.”

On the next page, you’ll be asked to enter your name, email address and to create and confirm a password. When finished, click “Next.”

Click “Agree and create account” and your PayPal account will be created.

How to Connect your Bank Account to your PayPal account:::::::::::::::::::::::

Log on to your account and click the “Wallet” option in the menu bar running along the top of the screen.

On the menu running down the left side of the screen, click the “Link a credit or debit card”.

Enter the card information you wish to link to your PayPal account and click “Link card” for debit card.

How to Send Money::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Log on to your account. Click Send & Request.

Enter the email address of the person you wish to send money to: nicholas@inscapetours.co.uk

Type in the amount you wish to send, click continue then press ‘Send Money Now’.