The Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612), one of the most fascinating men of the 17c, a great patron of the arts and sciences, was that oddity in his class, a man of intellectual and visual curiosity. Not altogether a success as a ruler, his reclusive nature led him to seek the company of scholars and artists rather than courtiers and politicians, and to retreat to the glories of his Wunderkammer, or Room of Wonders. Here he placed his collection of gems, medals, curiosities and the works of artists who pleased him and shared his delight in the natural world. Rudolf’s collection represented a radical antecedent of the modern museum, with objects ordered as if into a tangible encyclopedia. A devotee of the occult and of alchemy, he was simultaneously fascinated by science, and his court was sought by the rationalist scientific geniuses of the day such as the astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler, both concerned to further the radical discoveries of Copernicus a generation earlier. His artists fed off his scientists’ investigations into nature, and his natural scientists often relied on his artists to depict their discoveries. He was, in short, a patron of endless curiosity and imagination.

Gradually, very gradually, the work of Christian Krohg (1852-1925) has been emerging out of the shadow cast by his teacher, Edvard Munch. But now, bang! He has a major exhibition at the Musée D’Orsay in Paris where, rightfully so, the Norwegian Krohg belongs with the best, the most inventive, French art of the late 19c. In paintings of superlative skill Krohg can give us even more of an insight into late 19c Norwegian social concerns. He dives into the essence of his subject, whether a fragile convalescent girl, a group of prostitutes waiting to be examined in a police clinic, or a courageous fisherman in a rough sea, presenting his subjects up close like a modern film cameraman. Yet what might have been a grim inventory is elevated by dynamic postures, unbalanced compositions, and glorious colour, each hue in counterpoint with its neighbour. Christian Krohg was a profoundly humanist, libertarian and feminist painter. Through his works, the artist sought to raise awareness of critical political, moral and social issues, especially the status of women, the hard life of a Norwegian fishermen braving the rough seas of the North Atlantic, and the cruel, exhausting poverty that is the 19c seamstress’s lot.

It was, and is, the fate of many an artist’s model to be left holding the baby, with the artist/lover never to be seen again. That was not strictly the case with Caroline Joblaud, Matisse’s lover and model in the late 19c. After an early childhood with her mother, Marguerite was brought up largely by Matisse and his wife Amelie Parayre. The bond between the artist and his eldest daughter became essential to his life and his practice. From Matisse’s images of her childhood to her middle age after the end of WWII, Marguerite remained his most constant model and the only one to have featured in his work over several decades. This exhibition shows no fewer than 100 paintings and drawings, many of them never before seen in public, from French, Swiss, Japanese and American collections. Each work will reveal the miracle of Matisse: where other artists may need a plethora of lines to achieve their expressions, Matisse can present just one, one line so beautifully-judged that we read in it not only form and feature, but an entire life. We set Matisse’s profound works in the context of those by other artists depicting their children, from Gainsborough to Monet and Picasso.

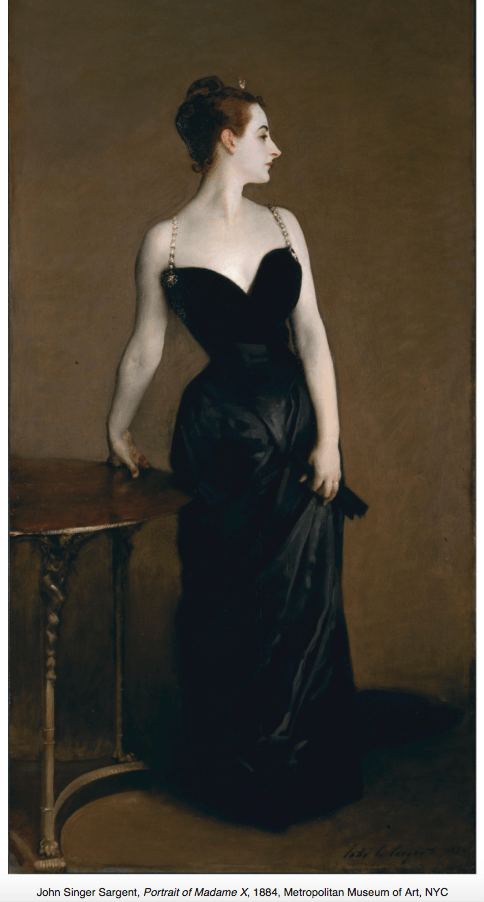

John Singer Sargent, son of an American doctor, was born in Florence and arrived in Paris aged 18 in 1874, the very year of the first Impressionist Exhibition. He was to learn quite literally at the feet of Monet, and to build on Impressionist brushstrokes to create some of the most vibrant and vital portrait, landscape and water studies of his generation. His seminal decade in the French capital culminated in his 1884 masterpiece portrait of `Madame X’, embroiling him in an extraordinary succès de scandale: the thin-shoulder-straps (about which there is a tale), and flushed skin of his subject seems to have been too much even for Parisians. Indeed in Sargent at his best there is an erotic charge, a life spirit, not always present in his Impressionist masters. The scandal persuaded Sargent to move to England where he established himself as the country’s leading portrait painter. He took this life spirit with him on his extensive travels to Italy (particularly Venice, of whose shifting fluidity he became one of the greatest masters), the Netherlands, and Spain where he revealed the passion of the flamenco dancer, El Jaleo, now a focal point of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

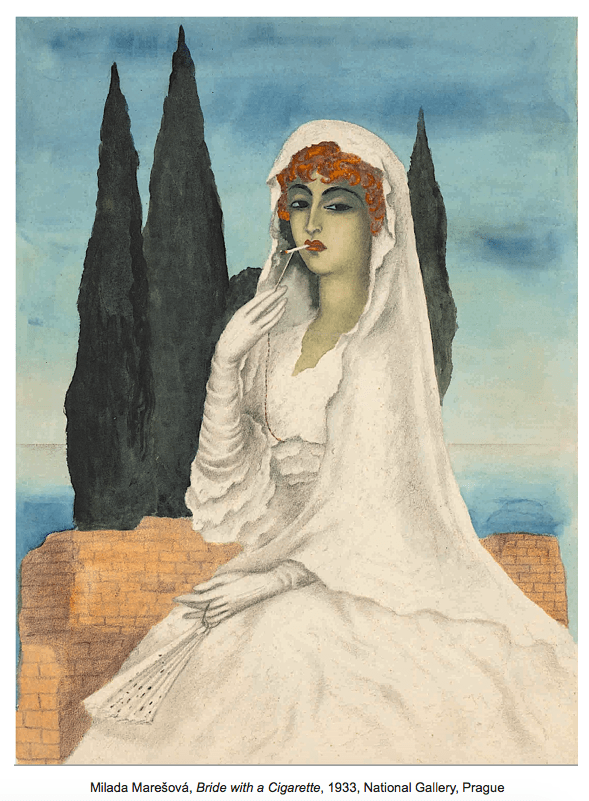

Radical! encourages visitors to think differently about the practice of what we call modernism in painting and sculpture, that is, to see it as multivoiced, international, and contradictory. Just as Picasso, Matisse, and Miro each had a unique voice, each approaching their work with different concerns, so did the women artists of this exhibition. Freed of male prescriptions, these sixty artists from more than twenty countries, Belgium, Italy, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Germany, America, Poland, and 13 other countries carefully chosen for this exhibition, are enabled to hold a conversation on their own terms. As well as works by those now quite well-known, such as Sonia Delaunay, Alexandra Exter, Kathe Kollwitz and Alice Neel, other artists’s names trip less easily off the tongue: Gertrud Arndt, Katarzyna Kobro, Marlow Moss and Fahrelnissa Zeid. Regardless of their media, whether textile designs, sculptures, prints, drawings, photographs, or film, these artists are united by their search for new forms of expression and representation, as well as their determination to redefine artistic, social and possibly even personal boundaries. They sound a particularly feminine clarion for art which should be not just modernist in style, but which should challenge the political as well as artistic status quo in unusual, often thrilling, ways.

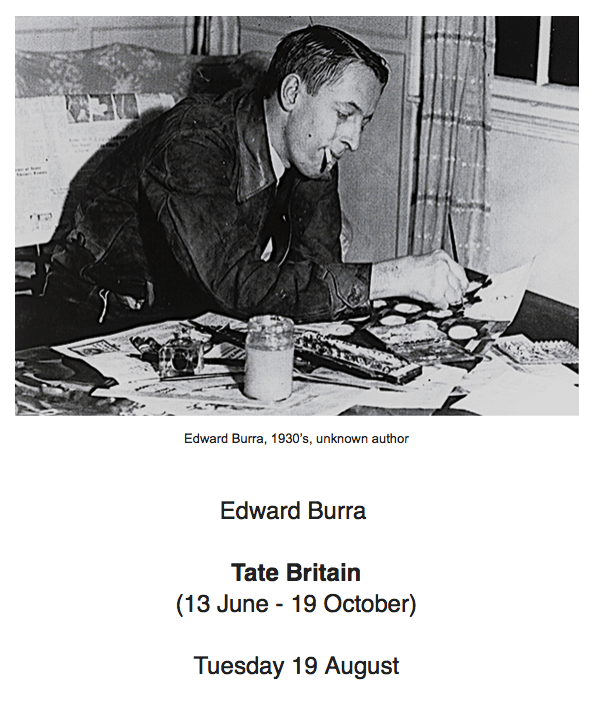

Partly because his work is so little known, and partly because it is impossible to pigeonhole into an ‘ism’, Edward Burra (1905-1776) is the great, thrilling, surprise of British 20c painting. Exceptional amongst British artists, in his early paintings of the rough, magnificently jazz-driven fast world of Harlem New York, the louche Paris underbelly of the Place Pigalle in Paris; and the prostitutes of the docks of Marseilles, Burra painted dark thrillers of urban life in the margins and the gutters. Because he signed the Surrealist Manifesto in 1936, made Surrealist collages, and sometimes hid faces behind Ernst-like bird-masks, art historians have tended to categorise him as a Surrealist (and he hated categories), but he was far more than that: he was a Realist too, always looking for the essence, be it the macabre or the beautiful. A master of watercolour, he pushed the boundaries of this traditionally delicate medium to create bold imaginative works influenced by his response to cataclysmic world events, including the Spanish Civil War, WWII, and the impact of post-industrial revolution on marginalized communities. One of the most distinctive artists of the entire 20c, his talents included everything from stage and costume design for ballet, opera and theatre to otherworldly interpretations of English landscapes.

Jean-Francois Millet makes of the most ordinary scenes in the countryside-wheeling a barrow, planting potatoes, saying the angelus in an open field- something not only heroic and suitable for the walls of the Paris salon, but something which can satisfy the eye of a connoisseur of Greco-Roman statuary. He does this, as did great ancient Greek masters of athletic statuary, by drawing our attention to gesture, to physical effort, even if that means depicting the winnowing of grain rather than launching a discus. Our focus is on the wrinkles of a toil-beaten wrist, the forward lurch of the body wheeling a barrow out of a farmyard, or the swinging motion of a sower on a Norman field. Was Millet a political revolutionary? Certainly the tricolor of red white and blue appear often enough in his paintings, and there is little wonder that his name is linked with that of Courbet as one of the fathers of French Realism which led eventually to Impressionism and much later the kitchen sink school. But social revolution is not as important for him as artistic revolution: helping us see the heroic and the instructive in the ordinary.

Information:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

‘Summer Exhibitions 2025’ is a Zoom course ( * for which we offer support to access) which has been developed by Louise Friend and will be presented by Nicholas Friend. It is held on Tuesdays, beginning on Tuesday 15 July 2025 at 5pm and ending on Tuesday 26 August 2025 at 5pm. Please note the time of 5pm: Nicholas will be lecturing from California (at 9am his time) for the duration of this course.

If you book for the course but cannot manage a particular date, then be assured we will be sending recordings of sessions to all registered participants. Each session meets from 15 minutes before the advertised time of the lecture, and each lasts roughly one hour with 15 minutes discussion.

COST: £350 for all seven for members, £420 for all seven for non-members. All sessions are limited to 21 participants to permit an after-lecture discussion session.

Please make your payment to Friend&Friend Ltd by bank transfer to our account with Metrobank, bank sort code 23-05-80, account number 13291721 or via PayPal to nicholas@inscapetours.co.uk, or credit/debit card by phone to Henrietta on 07940 719 397. She is available on Tuesdays or Thursdays between 2-5 pm.

How to Set Up a PayPal account::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Click on this link: https://www.paypal.com/uk/home

In the upper right-hand corner of the screen, click “Sign up.”

On the following screen choose “Personal account” and click “Next.”

On the next page, you’ll be asked to enter your name, email address and to create and confirm a password. When finished, click “Next.”

Click “Agree and create account” and your PayPal account will be created.

How to Connect your Bank Account to your PayPal account:::::::::::::::::::::::

Log on to your account and click the “Wallet” option in the menu bar running along the top of the screen.

On the menu running down the left side of the screen, click the “Link a credit or debit card”.

Enter the card information you wish to link to your PayPal account and click “Link card” for debit card.

How to Send Money::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Log on to your account. Click Send & Request.

Enter the email address of the person you wish to send money to: nicholas@inscapetours.co.uk

Type in the amount you wish to send, click continue then press ‘Send Money Now’.